Philosophy is naturally solicitous of music. Plato and Confucius both try to track down the ideal music to inculcate the virtues of justice and human-heartedness. Nietzsche, at both the beginning and end of his philosophical career, looks to opera as the supreme source of spiritual renewal, first to Wagner and then, splendidly, away from Wagner to Bizet (Carmen, he observes, turns you into a masterpiece when you listen to it). Nietzsche’s mentor Schopenhauer famously hears in wordless music the otherwise inexpressible essence of everything. Leibniz speculates–beautifully, weirdly–that when God sings to Himself, He croons algebra. Every philosophical masterpiece seems to have its own unique musical sound, often one that hasn’t quite been composed: Adorno argues that Descartes’ lonely “I think, therefore I am” prefigures the rise of the violin as a major voice.

What is the musical form that fits our quintessentially American philosophy?

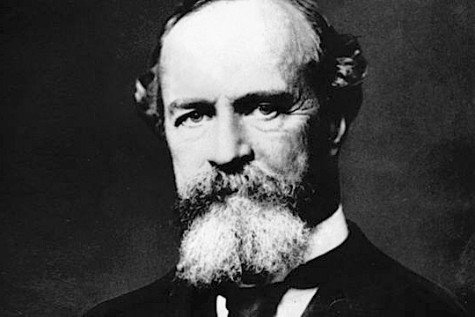

In the next few posts I want to work out an idea that’s been on my mind: namely, that William James is the American thinker whose philosophy is the most steeped in the inner meaning of the blues, and whose prose–especially the essays–is the most life-affirming, pluralistic, individualistic, jazzful writing we possess. Moreover, I think that his philosophy gives us a key to think about the inner significance of jazz. In the dazed aftermath of the Civil War William James found a philosophical way, strikingly similar to the musical way of the early jazz masters, of reconciling democratic freedom and spiritual nobility. If we allow for Jorge Luis Borges’s point that great works modify our conception of past and future, James’s “What Makes a Life Significant” (1899) is a strong precursor to Ellington’s “Concerto for Cootie” (1940).

In a notorious passage from The Varieties of Religious Experience, in the chapter called “The Sick Soul,” William James cites a typical case of “panic fear” from a mysterious French diary passage, which he “translate[s] freely.” When Varieties, a few years after its original publication, was being rendered into French, the translator requested the original passage. James wrote back that he must be content with the English, since the case–“acute neurasthenic attack with phobia”–was secretly James’s own.

I went one evening into a dressing-room in the twilight to procure some article that was there; when suddenly there fell upon me without any warning, just as if it came out of the darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence. Simultaneously there arose in my mind the image of an epileptic patient whom I had seen in the asylum, a black-haired youth with greenish skin, entirely idiotic, who used to sit all day on one of the benches, or rather shelves against the wall, with his knees drawn up against his chin, and the coarse gray undershirt, which was his only garment, drawn over them inclosing his entire figure. He sat there like a sort of sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes and looking absolutely non-human. This image and my fear entered into a species of combination with each other. That shape am I, I felt, potentially. [. . .] There was such a horror of him, and such a perception of my own merely momentary discrepancy from him, that it was as if something hitherto solid within my breast gave way entirely, and I became a mass of quivering fear. [. . .] In general I dreaded to be left alone. I remember wondering how other people could live, how I myself had ever lived, so unconscious of that pit of insecurity beneath the surface of life. My mother in particular, a very cheerful person, seemed to me a perfect paradox in her unconsciousness of danger, which you may well believe I was very careful not to disturb by revelations of my own state of mind . . . [T]he fear was so invasive and powerful that if I had not clung to scripture-texts like “The eternal God is my refuge,” etc., “Cone unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy-laden,” etc., “I am the resurrection and the life,” etc., I think I should have grown really insane.

James draws from the darkest night of his soul a profound blues-understanding, which thoroughly colors and humanizes his life-affirming, American philosophy. The pallor of this blues-understanding is all over his philosophical work. A chapter rarely passes where James’s prose doesn’t tremble with his commonality with the mad, the sad, and the sick.

The normal process of life contains moments as bad as any of those which insane melancholy is filled with, moments in which radical evil gets its innings and takes its solid turn. The lunatic’s visions of horror are all drawn from the material of daily fact. Our civilization is founded on the shambles, and every individual existence goes out in a lonely spasm of helpless agony. If you protest, my friend, wait till you arrive there yourself!

He doesn’t just note suffering abstractly but makes you feels in your bones just how it rolls round in the very course of life: “That life is not worth living the whole army of suicides declare–an army whose roll-call, like the famous evening gun of the British army, follows the sun round the world and never terminates. We, too, as we sit here in our comfort, must ‘ponder these things’ also, for we are of one substance with these suicides, and their life is the life we share.” James’s compassion, with something like Buddhist abandon, runs to the very springs of suffering.

When you and I, for instance, realize how many innocent beasts have had to suffer in cattle-cars and slaughter-pens and lay down their lives that we might grow up, all fattened and clad, to sit together here in our comfort and carry on this discourse, it does, indeed, put our relation to the universe in a more solemn light. “Does not,” as a young Amherst philosopher (Xenos Clark, now dead) once wrote, “the acceptance of a happy life on such conditions involve a point of honor?” Are we not bound to take some suffering upon ourselves, to do some self-denying service with our lives, in return for all those lives upon which ours are built? To hear this question is to answer it in but one possible way, if one have a normally constituted heart.

After rehearsing Leibniz’s account of how the “best of all possible worlds” can contain so many damned souls, James chides the great philosopher for a “feeble grasp of reality . . . whose cheerful substance even hell-fire does not warm.” As a counterweight, he sympathetically lingers over the last days of a Cleveland man who committed suicide by drinking carbolic acid. A student of James once fondly recalled how in a fit of passion he declared twinklingly to the class, “Gentlemen, as long as one poor cockroach feels the pangs of unrequited love, the world is not a moral world.”

Part II is here.

Pingback: The Jazz of James, Part II: Jazz as Pragmatism | Billy and Dad's Music Emporium

Pingback: The Jazz of James, Part III: Jazz as Pluralism | Billy and Dad's Music Emporium

Pingback: The Jazz of James, Part IV: The Gospel of Jazz | Billy and Dad's Music Emporium

Pingback: The Jazz of James, Part V: The Deepest Human Life | Billy and Dad's Music Emporium