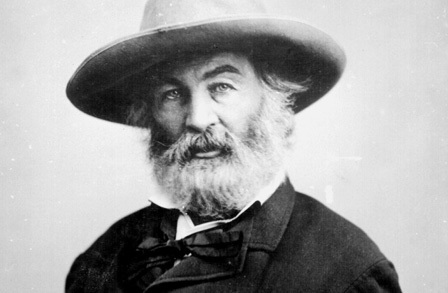

I go through phases where I all I want to hear is Duke Ellington. Listening to him is a never-ending task: he wrote over a thousand pieces and recorded most of them multiple times, always re-envisioning them according to the specifications of his band, his audience, and his own sense of artistic integrity. It’s hard to think of another composer from any tradition who crams into his music so much of real human life, the kind with both dirt under the fingernails and dreams on the brain. Pondering his unparalleled ability to draw on and draw out the selfhood of his prickly musicians and the bustling Americans around him, I just reread Whitman’s “Song of Myself.”

When I came to one of my favorite parts, section 26 on music, I was flabbergasted to find that Whitman too had been immersing himself in Ellington’s vast oeuvre: our bard was up ahead, waiting for me–as usual. Here it is, annotated with the Ellington pieces he must have been listening to.

I hear bravuras of birds, bustle of growing wheat, gossip of flames, clack of sticks cooking my meals, [“Sunset and the Mockingbird,” “Warm Valley, “Swamp Fire,” the humming of Mahalia Jackson at the end of “Come Sunday”]

I hear the sound I love, the sound of the human voice, [Ivie Anderson, Louis Armstrong, Rosemary Clooney, Marion Cox, Kay Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Al Hibbler, Herb Jeffries, Bette Roche, Jimmy Rushing, Frank Sinatra, et al.]

I hear all sounds running together combined, fused or following, [the famous “Ellington effect”]

Sounds of the city and sounds out of the city, sounds of the day and night, [practically all of Ellington; some of my lesser-known favorites: “Lull at Dawn,” “Eerie Moan,” “Lost in the Night,”]

Talkative young ones to those that like them, the loud laugh of work-people at their meals, [“Saturday Night Function,” “Rent Party Blues,” “I Love to Laugh”]

The angry base of disjointed friendship, the faint tones of the sick, [“Up and Down,” “East St. Louis Toodle-oo”]

The judge with hands tight to the desk, his pallid lips pronouncing a death-sentence, [the Anatomy of a Murder soundtrack]

The heave’e’yo of stevedores unlading ships by the wharves, the refrain of the anchor-lifters, [“Stevedore Stomp”] . . .

The steam-whistle, the solid roll of the train of approaching cars, [“Choo-Choo,” “Daybreak Express,” “Way Low,” Across the Track Blues,” “Happy Go-Lucky Local,”]

The slow march play’d at the head of the association marching two and two,

(They go to guard some corpse, the flag-tops are draped with black muslin.) [“Black and Tan Fantasy”]

I hear the violoncello, (‘tis the young man’s heart’s complaint,) [Oscar Pettiford]

I hear the key’d cornet, it glides quickly in through my ears,

It shakes mad-sweet pangs through my belly and breast. [probably Rex Stewart]

I hear the chorus, it is a grand opera, [the Sacred Concerts]

Ah this indeed is music – this suits me. [“It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing”]

A tenor large and fresh as the creation fills me,

The orbic flex of his mouth is pouring and filling me full. [undoubtedly Ben Webster]

I hear the train’d soprano (what work with hers is this?) [the Swedish Alice Babs]

The orchestra whirls me wider than Uranus flies, [“Moon Maiden,” “Dance of the Flying Saucers”]

It wrenches such ardors from me I did not know I possess’d them, [“I Don’t Know What Kind of Blues I Got”]

It sails me, I dab with bare feet, they are lick’d by the indolent waves, [the small-group version of “A Sailboat in the Moonlight”]

I am cut by bitter and angry hail, I lose my breath, [the Newport “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue”]

Steep’d amid honey’d morphine, my windpipe throttled in fakes of death, [Billy Strayhorn’s “Blood Count”]

At length let up again to feel the puzzle of puzzles, [“What Am I Here For?”]

And that we call Being.

And that we call Duke Ellington. In fact, that is just the beginning. You could probably annotate a big chunk of Whitman’s long lists with their musical counterparts in Ellington, whose 1,001 compositions could be collected under the title “Songs of Ourselves.” Both artists have their valves wide-open to the energies of the vast continent through which they ramble. Both artists inherently believe, in the words of William James, that “the deepest human life is everywhere,” and that American democracy is the natural fit for our plural depths. Both artists have faith that a better, truer, juster America can be chanted into existence by their music.

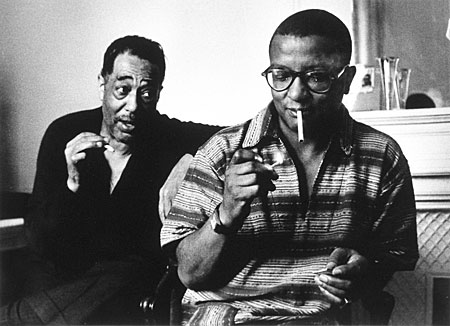

Whitman boasts that he contains multitudes. Ellington contains not just imaginative but literal multitudes. To speak of his music is to speak of the hundreds of musicians whose improvisations and ideas are seamless parts of Ellingtonia, of the dancers at the Cotton Club whose choreography shaped his early compositions, of the audiences he redesigned his songs to please, and, most pressingly, of Billy Strayhorn, Duke’s other half as a composer.

As a twenty-three year-old young man playing piano in a Pittsburgh drugstore, Strayhorn lucked into a meeting with Duke in 1938. He took advantage of the moment (Duke was getting a massage) to play “Sophisticated Lady” on the piano note for note as the master had played it earlier that night; then he played it again à la Strayhorn. Duke loved the display of ingenuity and invited the kid out to his place in Harlem. To impress him again, Strayhorn made up a ditty out of Duke’s directions on how to get there: “Take the A Train.” How fitting that the signature song of the Ellington orchestra was written by somebody other than Ellington, by somebody trying to find his way to Duke’s place!

Take the ‘A’ Train was written to address the confusion between the “D” train and the “A” train routes. The “D” train went through uptown on the way to the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. The “A” Train went directly to Harlem. Both trains ran on the Independent Line of the New York Subway. So if you wanted to go to Sugar Hill in Harlem, you had to take the “A” Train instead of the “D” train. This explanation came from the mouth of Billy Strayhorn.